Part 2: Energiewende? More Like, Energieweimar

Germany's Glorious Energy Suicide Part 2: Deindustrialization

Last week, we detailed how the German Energiewende has resulted in rising electricity costs for German families and businesses and hinted at the deindustrialization stemming from German energy policies.

Today, we’ll look at some of the economic data coming out of Germany and connect the dots to how Germany’s energy policies have contributed to the country’s current economic predicament.

The “Sick Man of Europe” Returns

In 1998, economist Holger Schmieding labeled Germany the “Sick Man of Europe” when its economic growth fell below that of other members of the Eurozone due to the high cost of reuniting East and West Germany.

However, in the following decades, Germany became the strongest economy in Europe, thanks largely to its industrial prowess. Now, the German economy is struggling under the yoke of high taxes, regulatory barriers, and high energy prices, reviving the country’s sick man moniker and mirroring the issues that plagued the Weimar Republic.

As

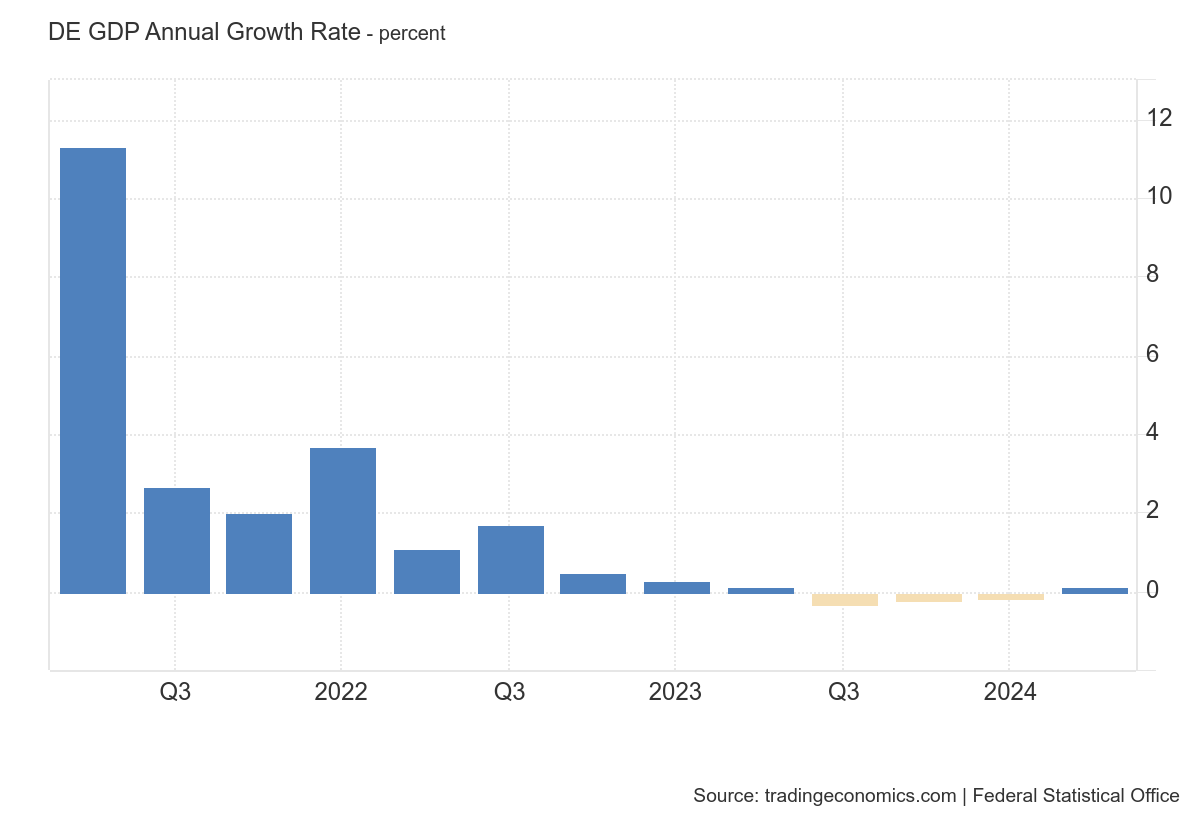

noted in his excellent and conveniently-timed piece, Catching the Bug, the German economy has performed poorly since Q1 2023, and it’s poised to grow more slowly than all OECD member states in 2024 except the United Kingdom.

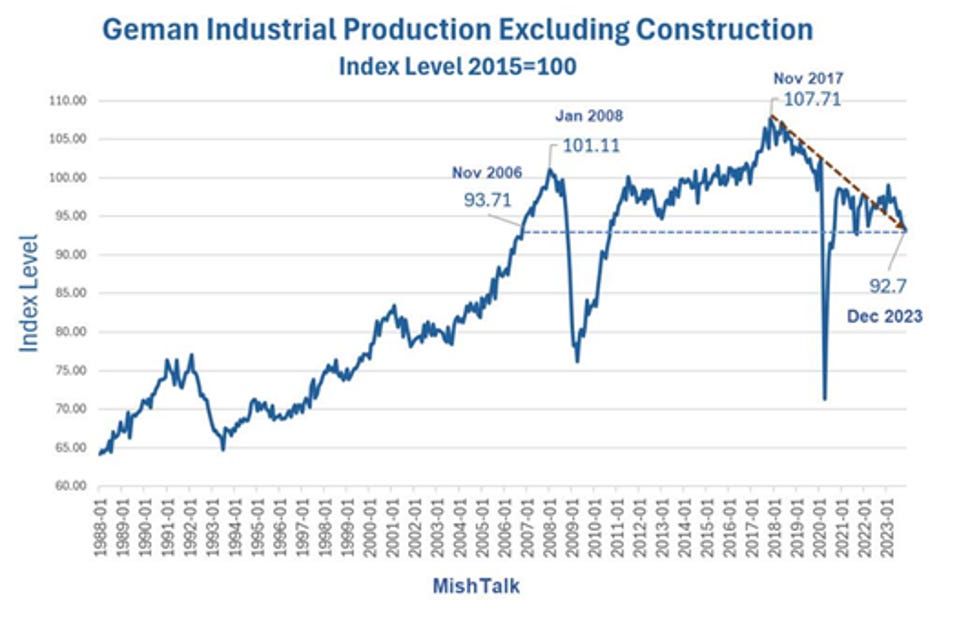

In Forbes, Tilak Doshi notes Germany’s industrial production peaked in November of 2017 and, by the end of last year, had fallen to a level last seen in 2006 outside of the global financial recession and Covid-19 years. Its industrial sector contracted by almost 14 percent in the six years ending December 2023.

Sluggish economic growth is now weighing on consumer sentiment. The Wall Street Journal notes:

The forward-looking consumer-climate index for Germany, published Tuesday by research group GfK and the Nuremberg Institute for Market Decisions, forecasts confidence to fall 3.4 points to minus 22.0 points in September. That snapped back from the improvement seen in August, and is considerably weaker than the consensus of economists polled by The Wall Street Journal, who expected it to be at minus 18.4.

For consumers, income expectations for the next 12 months fell significantly. As news about weakening job security makes consumers more pessimistic, it reduces the chances for a quick turnaround in consumer confidence.

Natural Gas

Before we scroll through economic doom in Deutschland, we need to discuss the role of natural gas in Germany’s economic woes.

In 2021, nearly 34 percent of all the natural gas used in Germany was used by industrial consumers.

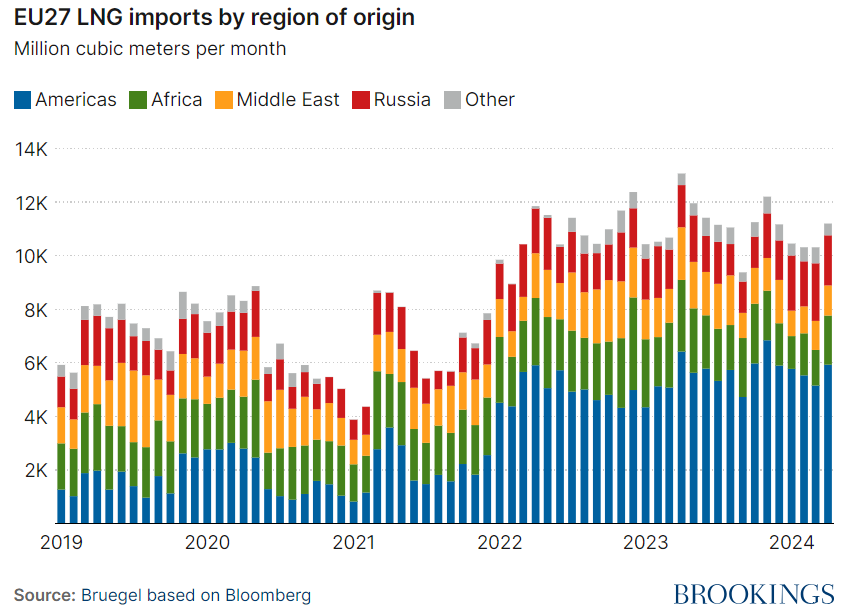

Germany is among the world’s biggest natural gas importers, importing around 95 percent of its gas consumption. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia provided 55 percent of Germany’s natural gas, making Germany the largest buyer of Russian natural gas in Europe.

Germany’s domestic production accounts for just five percent of its annual consumption, and unlike the United States, the country foolishly banned hydraulic fracturing. As a result, Germany ensured its shale gas reserves, which are many times larger than its conventional reserves, would be kept in the ground.

As a result, the good old US of A is supplying the European Union with much of its gas, as the Americas account for about half of EU gas imports through much of this year.

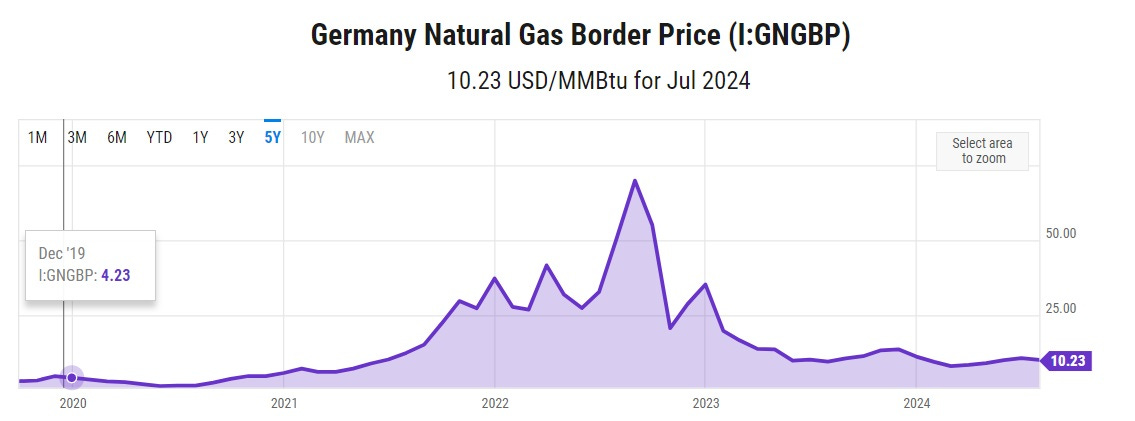

These imports have come at a cost, though. According to Y-Charts, German natural gas border prices in July were $10.23 cents per million British Thermal Units (MMBtu) compared to just $4.23 MMBtu in December 2019, harming the competitiveness of German industry.

Winter, for Industry, in Germany

The German economy heavily depends on exports in energy-intensive industries, with the automotive, chemical, mechanical engineering, and electrical industries constituting the largest manufacturing sectors.

Data from Statista show that in 2023, 24.3 percent of Germany’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) came from the production sector, with another 5.4 percent coming from the construction sector. Germany’s export ratio for manufactured goods was 48.4 percent, meaning about half the goods produced in Germany are sold abroad.

This export-driven model supports approximately 10 million manufacturing jobs in Germany, constituting 24 percent of the nation’s workforce. Unfortunately, German policy is threatening these jobs by making energy more expensive, and a recent survey found a third of German industrial companies were planning to boost production abroad rather than at home.

On Tuesday, Volkswagen, which employs almost 300,000 people in Germany, announced it was scrapping a range of labor agreements, including a guarantee of jobs until 2029 at six German plants, raising the prospect of layoffs and potential closures of two manufacturing facilities in Germany, a first in the company’s history.

Other companies in energy-intensive industries are following suit.

In October 2023, Bloomberg reported that German chemical giant BASF planned to cut investment by almost 15 percent over the next four years and chemical firm Lanxess AG is slashing 7 percent of its workforce as high energy prices and cratering global demand continued to drag on the industry.

German steelmaker Kloeckner & Co SE announced it was cutting 10 percent of its workforce in European distribution after its 2023 guidance and Thyssenkrupp AG, the largest steelmaker in Germany, announced it would cut its steelmaking in Germany by 20 percent by scaling back production at Duisburg plant, which will result in job losses.

Germany’s trend toward becoming the “Rust Belt on the Rhine” prompted Bloomberg to speculate that Germany’s days as an industrial superpower are coming to an end. In total, 82 percent of German companies surveyed by the Federation of Germany Industries cited energy security and costs as at least a moderate reason for moving their investments abroad, with 59 percent of firms saying energy was a strong or very strong factor in their decisions.

Springtime, for America

Germany’s self-inflicted losses have been America’s gain. German firms, especially petrochemical manufacturers, are now moving to the United States.

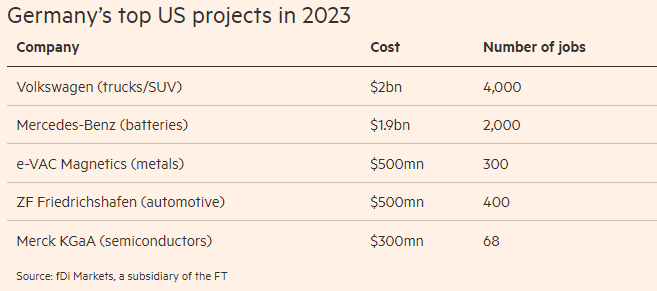

According to The Financial Times, German companies announced a record $15.7 billion of capital commitments in US projects last year, up from $8.2 billion a year earlier, according to data compiled by fDi Markets, a subsidiary of the Financial Times, dwarfing the $5.9 billion pledged in China.

The Financial Times continued:

German companies announced 185 capital projects in the US in 2023, of which 73 were in the manufacturing sector. The largest project was a $2 billion investment by Volkswagen’s Scout Motors electric vehicle subsidiary in Columbia, South Carolina.

These expansions in the United States are projected to bring nearly 7,000 jobs to the country.

German companies have shown signs that they will continue to invest in the United States. BASF plans to invest over $4 billion in North America between 2023 and 2027, including major expansions of petrochemical plants in Louisiana and Ohio.

As the Times article stated, “BASF is a key example for investors and politicians concerned about creeping deindustrialization in Germany, having announced a “permanent” downsizing of its headquarters in Ludwigshafen, with thousands of job cuts and plant closures following the surge in European energy prices when Russia invaded Ukraine.”

Conclusion

The only thing worse than being completely wrong is being insufferably smug about how right you were along the way. No nation has been as wrong or as insufferable on energy issues over the last decade as Germany, and it’s all gloriously imploding around them.

Germany’s Energiewende is turning into the Energieweimar, with job-creating companies leaving the country and impoverishing the citizens left behind. While we feel for those who will lose their livelihoods in the coming years, it’s a reminder that elections have consequences, and electing leaders who are obsessed with fighting climate change will result in an unlivable business climate.

Luckily for us, the United States has fewer regulations and lots of cheap natural gas. Who’s laughing now, Heiko?

Enjoy this live look at the future of America stealing Germany’s jobs.

Like this piece if you want to drink Germany’s milkshake.

Share this piece and subscribe if you want to drink it all up.

What is Demand Response and How Are Virtual Power Plants Connected by

. A great primer on virtual power plants and demand response.German govt should combat energy poverty with targeted support for low-income households – report by Clean Energy Wire. If wind and solar are so cheap, why is energy poverty so rampant in Germany?

Germany is losing its status as the engine of the EU economy by the GMK Center. The German economy – the largest in the European Union with a GDP of about €4.5 trillion by 2023 – has turned from a locomotive into a brake on the European economy.

Thank you EBBs. An article on Europe's energy can be read here, as I reported on Irina Slav's substack: https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-energy-bills-germany-brussels-pipeline-prices/ It seems as though the approach to the downward plunge of the vehicle that is Europe's energy is to step on the gas.

A story already related a while back on Doomberg's substack: in about 2005, through an odd circumstance, I (a complete nonentity, let's be clear) was at a dinner party in London's Belgravia, in conversation with a fascinating and charming man man-of-the-world who introduced himself as "a neighbour from across the square", who turned out to be the German ambassador to the UK. I asked him whether he thought the Russians would use energy as a political weapon (which I regarded as a no-brainer), to which he replied "no". To my intense frustration ever since, we got parted and I never got to ask him why he thought so. I note that his boss, then Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, made money from Russian energy, being on the board of Nord Stream AG and Rosneft. I reckon the final score was Nonentity 1: Ambassador 0. Funny old world.

Germany trail blazes 'net zero' and Russophobia with the resultant effect on its economy.

But far worse is the UK who could see this happening in real time in Germany, and decided to double down in its efforts to go even further into the pit. Not that it had nearly as much manufacturing or heavy energy users to loose, but its now doing its best to finish off what was left.