Why Don't They Turn the Wind Turbines Up?

Your guide to debunking the myth that it's not the wind's fault

“Why don’t they turn the wind turbines up?” -Inquiring minds want to know

There is a truism among wind and solar advocates that these resources are never to blame for anything bad that happens on the electric grid.

During Winter Storm Uri, for example, wind advocates claimed low wind output was not even partially to blame for rolling blackouts in ERCOT. Jesse Jenkins of Princeton University famously tweeted that the wind is “reliably unreliable.”

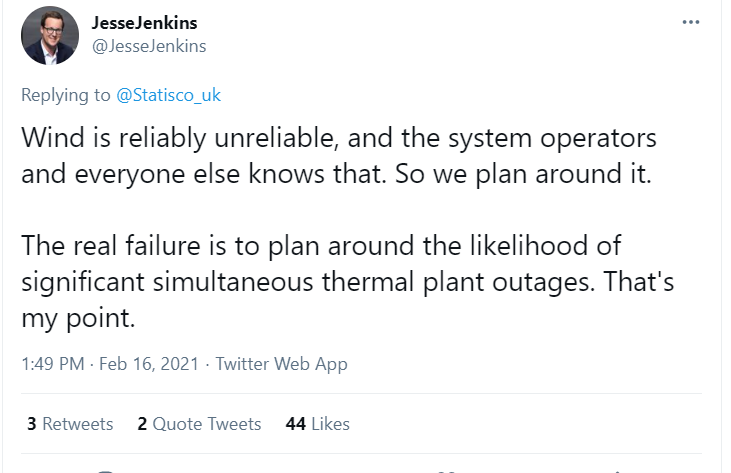

Inevitably, wind and solar advocates will point to problems with every other resource, arguing that coal piles can freeze, natural gas pipelines can malfunction, interrupting supply and causing gas units to go down, and nuclear units can unexpectedly trip offline.

These arguments are correct - any power plant technology can experience problems - but they also reek of Whataboutism.

When dispatchable power plants go offline, it is a bug with identifiable steps that can be taken to mitigate outages in the future. When wind and solar underperform expectations, it’s a feature resulting from the intermittency of the resource that can result in a shortage of electricity on the system.

If resource planners didn’t rely on wind and solar for reliability, arguments such as Jesse Jenkins’ would be more accurate. However, that isn’t the case.

Why Don’t They Turn the Wind Turbines Up

Rather than hold wind and solar accountable for the inherent intermittent energy they produce, wind and solar advocates want you to believe that not planning for thermal outages is the real culprit behind power shortages in renewable-heavy grids like ERCOT and CAISO. What they fail to admit is that “reliably unreliable” energy is the plan and has been for some time.

In every Regional Transmission Organization (RTO) around the country, wind energy is given some kind of capacity accreditation value—which is the percentage of total installed capacity that is expected to be available during peak demand. In ERCOT, for example, wind turbines have capacity values of 19 - 43 percent in the winter and up to 61 percent in the summer, depending on where it’s located in Texas (coastal, panhandle, etc.).

This means rather than expecting the wind to be reliably unreliable, ERCOT and other RTOs expect wind energy to reliably serve a percentage of peak demand.

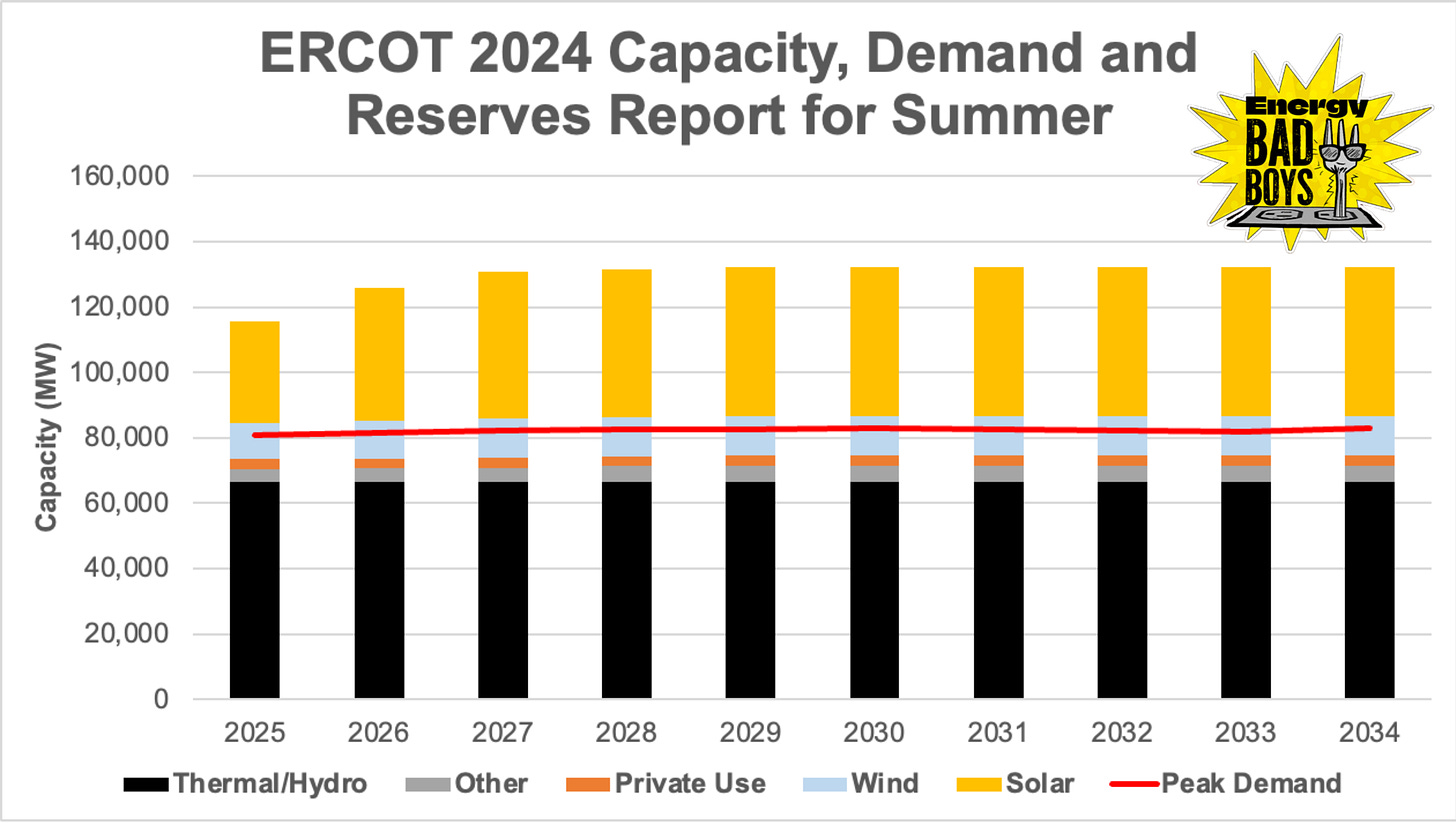

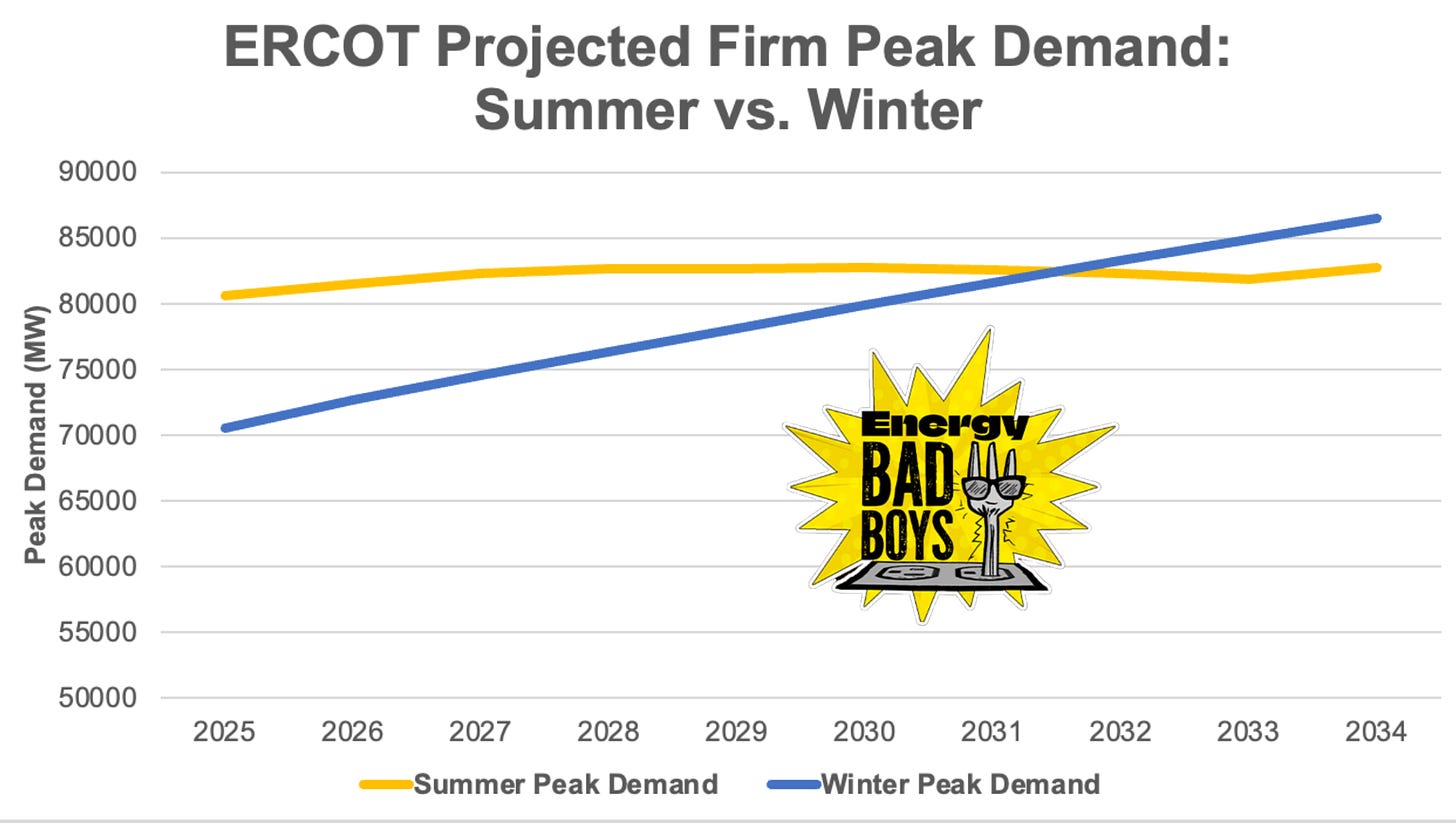

In fact, in the summer, the reserve margin in ERCOT—which represents a safety net in case of unplanned plant outages or unexpected higher demand—is made up entirely of intermittent wind and solar. As you can see in the graph below, the red line is the projected peak demand and everything above it represents the reserve margin.

In other words, because the reserve margin is entirely made up of wind and solar resources, ERCOT is dependent on intermittent energy sources showing up in the summer, which is a far cry away from planning for them to be “reliably unreliable.” By 2031, ERCOT reports show that this trend will hit the winter reserve margin, as well.

Wind Energy Underperforms Expectations

The problem with this is that wind energy routinely underperforms capacity accreditations.

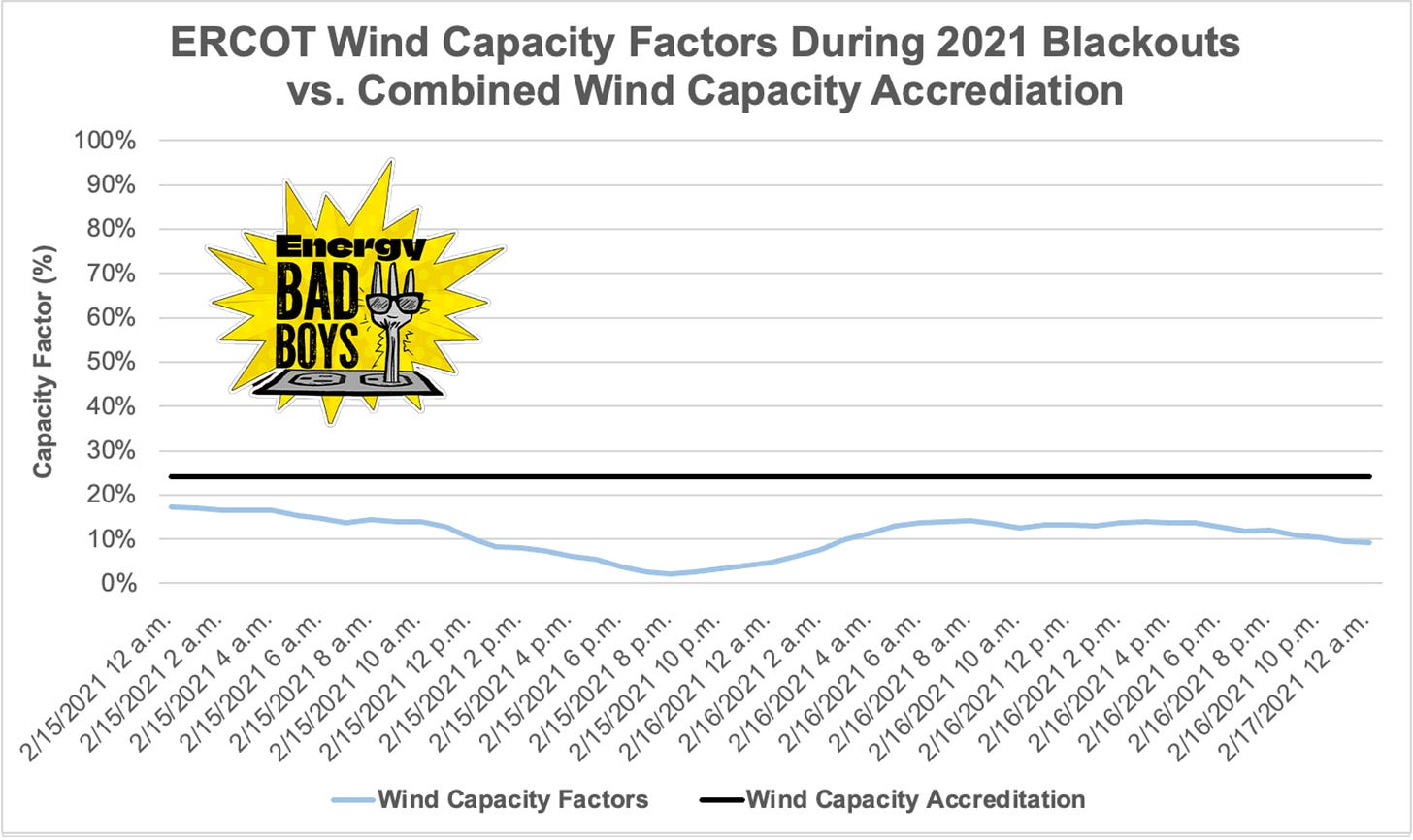

As the graph below shows, wind energy was producing nowhere near its capacity accreditation during Winter Storm Uri when the rolling blackouts ensued in Texas. At no point during the initial blackout was wind operating above its combined capacity accreditation of 24 percent (capacity-weighted) at the time.

This begs the question, “Why don’t they turn the wind turbines up?”

Obviously, they can’t, which is why giving wind any capacity accreditation for meeting peak demand is the equivalent of playing Russian roulette on the energy grid. This is why we refer to the capacity accreditation given to wind and solar as “phantom firm” resources. Maybe they show up, maybe they don’t.

A National Concern

Grid operators frequently warn that the continued rapid pace of resource retirements, EPA regulations further accelerating resource retirements, and an increasing reliance on wind and solar threaten grid reliability.

The problem here is that system operators are increasingly reliant upon wind turbines and solar panels showing up to work to meet their peak demands by giving them capacity values. In layman’s terms, they are expecting wind and solar to show up in some capacity to meet peak demand.

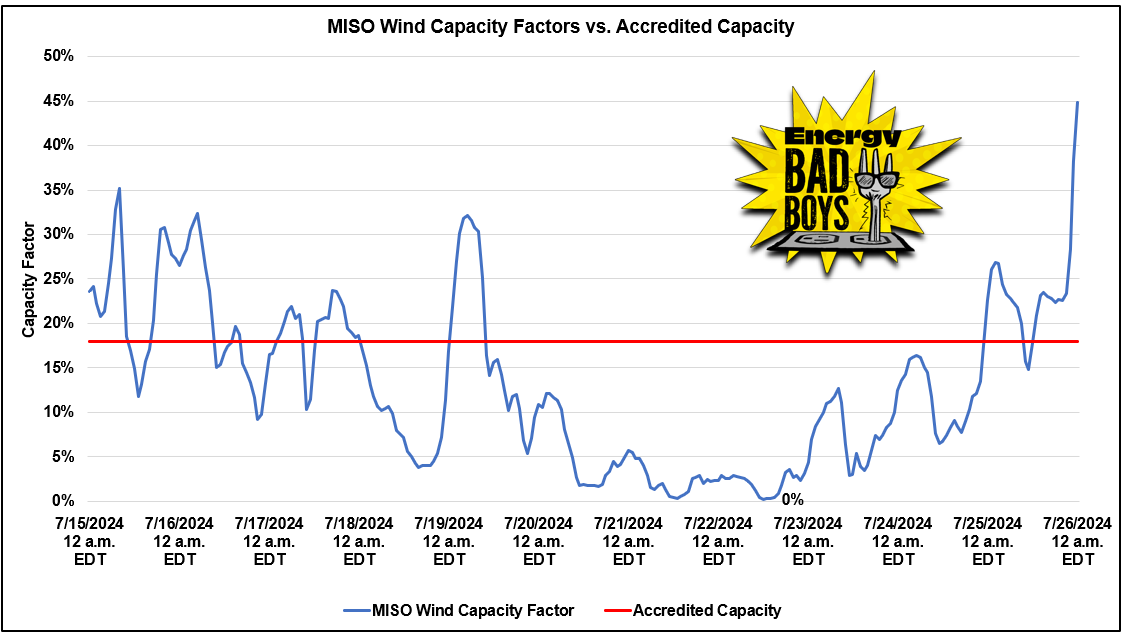

However, wind generation often experiences droughts, and it has been especially paltry in the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) region over the last two weeks.

The graph below, constructed with U.S. Energy Information Administration data, shows the hourly wind capacity factors in the region and compares it to the 18 percent capacity accreditation given to wind turbines by MISO.

Essentially, it shows that wind has been underperforming the grid operator’s expectations for 133 consecutive hours. Thankfully, the region has seen low electricity demand relative to the expected peak demand, allowing the lights to stay on despite the wind’s underperformance. Grid operators take huge gambles hoping that these droughts don’t occur during higher demand periods.

As we pointed out in our article Wind Drought Blackout, these are not isolated incidences.

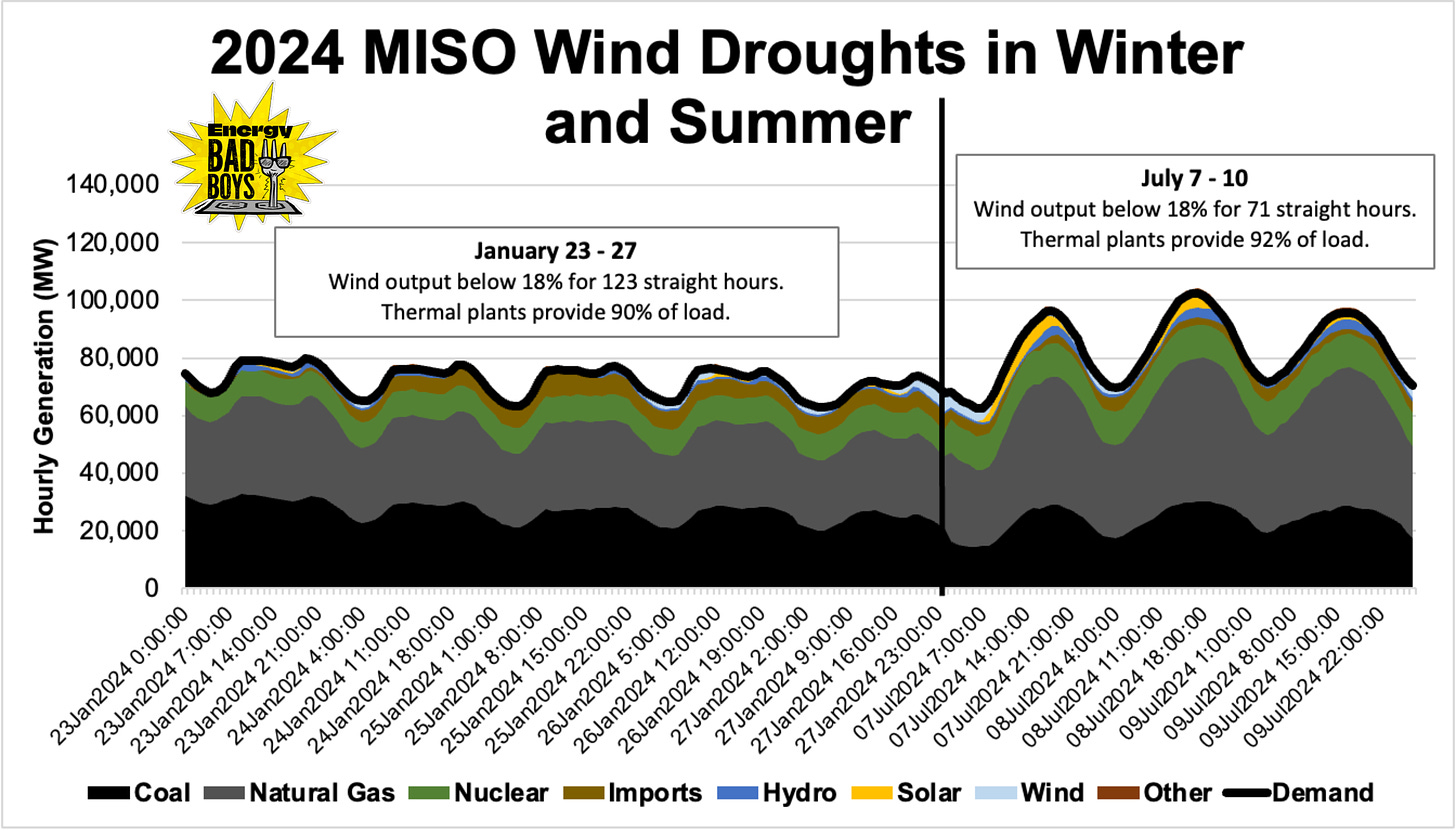

As you can see below, already in 2024, two major wind droughts occurred in different seasons. In January of this year, wind in MISO was performing at less than 18 percent of its potential output for 123 straight hours - or over 5 days - despite grid operators assigning it 52.2 percent capacity credit in winter months. Then, from July 7th to July 10th, wind was operating below its accredited capacity of 18 percent for 71 straight hours.

Thermal generation served over 90 percent of the system’s load during each wind drought.

While summer underperformance for wind and solar will be inconvenient, winter underperformance could be deadly. Currently, much of the nation experiences its peak electricity demand in summer for air conditioning. In the future, electrification of home heating will cause winter electricity demand to skyrocket, raising the stakes of relying on renewables to heat our homes.

For example, ERCOT is expected to be a winter-peaking system by 2032 due to the ongoing electrification of new homes.

Removing Roadblocks to Reliability

The situation looks grim, but there may still be time to head off the worst effects of our growing reliance on wind and solar generators.

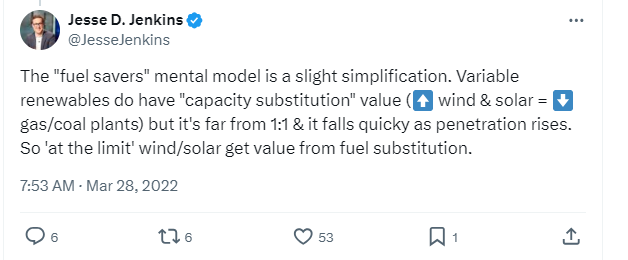

The obvious solution to this problem is to acknowledge the limited capacity value that wind and solar provide to the grid, as Jesse Jenkins did below, and greatly reduce the amount of accredited capacity these resources receive—perhaps to zero—from RTOs for purposes of system planning.

Another common sense solution is to require our electric grids to have enough dispatchable capacity on their systems to meet the projected peak demand, plus a margin of safety of more dispatchable capacity to account for frozen coal piles and nuclear plants tripping offline.

Natural gas plants should also be required to store fuel on-site, whether that be fuel oil or liquefied natural gas (LNG). If nothing else, wind and solar facilities should be required to pay for the cost of firming the grid to make up for their intermittency.

These changes, not the addition of more wind, solar, and battery storage, will enable grid planners to affordably “plan around the likelihood of significant simultaneous thermal plant outages” and ensure that disruptions in the natural gas supply don’t cascade into blackouts.

Conclusion

Our current energy policy can be described as “all gas and no brakes” in favor of wind and solar. At some point, the chickens will come home to roost. We will have more rolling blackouts if we continue to shut down reliable power plants and become increasingly reliant upon wind and solar showing up to work when we need them most.

When these blackouts occur, we can expect wind and solar advocates to turn on the spin cycle, pointing fingers at everything but the failure of their preferred resources to get the job done. When this happens, we encourage you all to pose the question: “Why don’t they turn the wind turbines up?”

Click Like, Share, and Subscribe if you think the wind turbines should be turned up to 11.

When You are Ready for that Generator by

: The first in a series of articles will run through the ins and outs of buying a generator. Become a paid subscriber to Energy Bad Boys to fund our generator purchases ;) Is the energy transition resource-constrained?: “One of the reasons for the anger is obvious: the turbine blade began disintegrating on Saturday evening and sent some 17 cubic yards of debris into the ocean. But the owners of Vineyard Wind didn’t notify officials in Nantucket until Monday at about 5 pm.”

If it’s not dispatchable it’s not capacity.

Thank you again EBBs. Your posts have a habit of bringing to mind the tongue-in-cheek comment of a younger and much brainier engineering colleague of years ago, referring to the difference between measured results and simulation: "Reality's got it wrong again".