EPA's Green Leap Forward

EPA's Doesn't Even Model Electric Reliability In Its Regulations

“Sometimes you eat the bar, and sometimes the bar, well, sometimes he eats you”- Sam Elliot in The Big Lebowski

Last month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released its finalized rules regulating carbon dioxide emissions from existing coal plants and new natural gas plants. The rules have garnered criticism from industry, grid operators, and lawmakers, including Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), who claimed the regulations would undermine grid reliability at a time when demand for electricity is expected to surge in the coming decades.

Given the fact that the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) is already warning that two-thirds of the country is at an elevated or high risk of blackouts in the next few years, you would think the EPA would carefully model the reliability impacts of its latest regulations to ensure they won’t make this problem worse. But, boy howdy, would you be wrong.

Why Look When You Can Leap?

According to EPA documents, the agency’s analysis of the impacts of its carbon dioxide regulations on new natural gas plants and existing coal plants does not take reliability into account. Instead, it performs a resource adequacy analysis. EPA writes:

The objective of this analysis is to provide insight into the resource adequacy impacts of the rule. EPA’s role in regulating emissions from electric generating units does not include specifying generation resource mixes or grid operations and planning practices. Thus, EPA does not conduct operational reliability studies.

Previously, EPA acknowledged that this isn’t a sufficient analysis to make sure the lights stay on:

“As used here, the term resource adequacy is defined as the provision of adequate generating resources to meet projected load and generating reserve requirements in each power region, while reliability includes the ability to deliver the resources to the loads, such that the overall power grid remains stable.” [emphasis added].” EPA goes on to say that “resource adequacy … is necessary (but not sufficient) for grid reliability.

What Is Resource (In)Adequacy?

To understand why this is such a problem, it helps to explain what a resource adequacy analysis is and discuss its limitations.

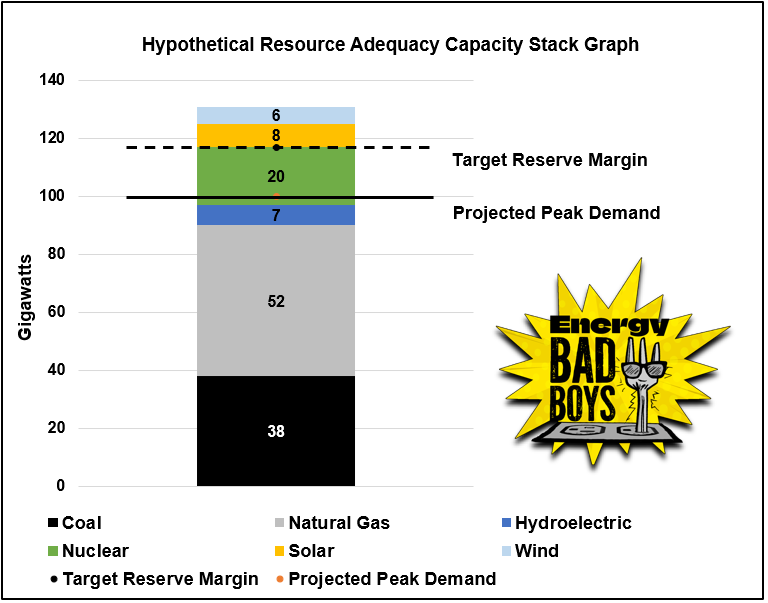

In its simplest terms, resource adequacy is kind of like pole vaulting. You need enough reliable power plant capacity to clear the bar—your projected peak demand—plus a margin of safety to keep the lights on.

In this analysis, each power plant in the stack is given a reliability rating, known as a capacity value, which allows grid planners to estimate the amount of electricity these plants can reliably produce when it is needed most.

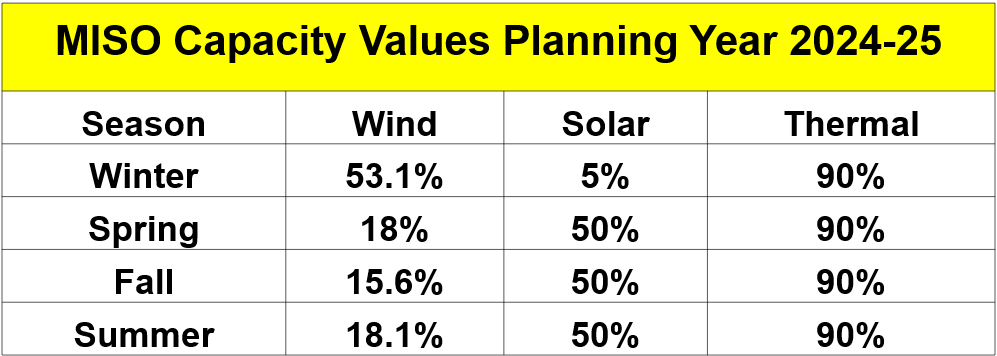

In the Midcontinent Independent Systems Operator (MISO), thermal plants, such as coal, nuclear, and natural gas, are given a high capacity value because they are dispatchable, and wind and solar receive lower ratings because grid operators can’t turn their wind turbines up or switch their solar panels to night mode.

The capacity values of these power plants, often measured in megawatts (MW) or gigawatts (GW), are multiplied by the capacity value percentage to get an estimate of the total amount of reliable capacity the plant is contributing to the grid.

These estimates are then totaled into a capacity “stack” to determine whether the available capacity can meet the projected peak demand plus a margin of safety, called the target reserve margin.

Smart grid operators make sure there is enough dispatchable power plant capacity on their systems to clear the bar of their projected peak demand and meet their reserve margin. If they want to “stack” wind and solar on top of this grid, it will add expense to the system but won’t compromise reliability.

However, as state carbon-free mandates, federal regulations, and subsidies have forced the premature retirement of coal plants and have incentivized the increased usage of wind and solar, grid operators are now beginning to rely on the capacity value of wind and solar to meet their projected peak demand and target reserve margins.

This, in our view, is a big no-no because these resources may or may not show up when you need them, which is why we refer to the capacity value of wind and solar as “phantom firm” resources. In essence, grid reliability is becoming more dependent on favorable weather conditions, which is a huge gamble.

EPA’s Phantom Firm Resources

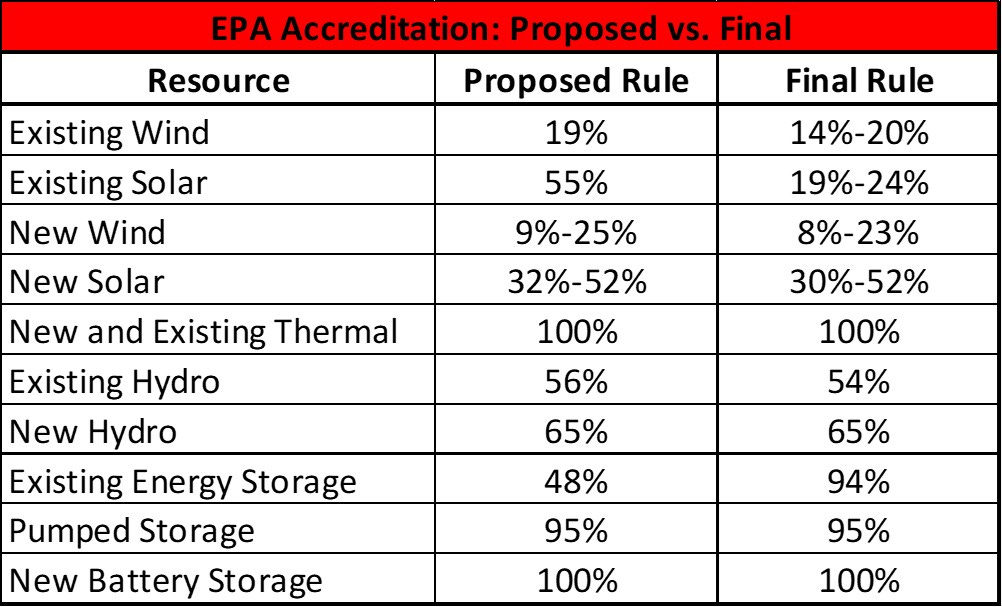

According to EPA’s own modeling of the MISO grid under the final rule, wind and solar are given generous capacity accreditations that may leave the region short of electricity when the weather doesn’t cooperate.

The table below shows the capacity values EPA gives each resource in the final rule. Notice that the EPA makes two unrealistic assumptions. First, it gives thermal resources a 100 percent accreditation, which overestimates the ability of the thermal fleet to provide power as it ignores routine maintenance outages and assumes they will be available 100 percent of the time. Second, it gives wind and solar generous accreditation that overstates the potential availability of these resources to meet peak demand.

EPA then uses these values to claim that it has cleared the bar, so to speak, when it comes to ensuring resource adequacy, even though the agency is relying on wind, solar, and battery storage to meet its peak demand obligations in MISO.

This begs the question, will EPA’s modeled MISO grid be able to provide reliable power around the clock to keep the lights on? Tune in to a future article to find out!

Thank you for reading Energy Bad Boys!

Subscribe so you know if you’ll need to buy a backup generator in the near future.

Share this article with your friends so they can buy one, too. Do not share this with your enemies ; )

Upgrade to paid so we can buy generators for our homes and produce content for you all regardless of whether the wind is blowing or the sun is shining.

The Energy Bad Boys were recently on the Energy News Beat podcast. Check it out!

The very first table of MISO capacity values for planning year 2024-2025 are nothing more than seasonal averages, except maybe solar is too high in spring through autumn. In other words these planning values are based on the hope that averages means something when operation is moment by moment. As I stated in some PSC testimony in February 2023 these average values are composed of days when the wind plant produces 35% and days when it produces just about as close to zero as anyone would fear, just as Pau says nearby. I pull plots of weekly generation throughout the year to show there is no season that doesn't display this sort of behavior -- and even in Wyoming where everyone talks about the terrible wind.

Under additional questioning in this hearing the utility admitted that the wind plant they are planning may actually produce only 10-20% of nameplate and contributes almost nothing to their looming adequacy gap but expense. They know. The PSC, though, didn't seem to tumble to the problem. The problem with the EPA might be they don't really tumble to it either; or it may be ideology.

The reason we have gotten by, so far, is that many regions still have quite a lot of excess coal and gas, while wind and solar have penetrated only about 20% into the grid supply. MISO's own analyses shows that things can go on smoothly until about 30% wind/solar and then operation of the grid changes markedly. Time will tell.

Over reliance on natural gas will re-create the supply issues of the 1970s (when over-reliance on petroleum liquids was a problem), and will raise utility bills because natural gas prices are volatile. But, in the longer run folks are planning on 100% wind/solar + magic.

I can share the link if anyone is interested. Here in the UK we have around 30gw of wind capacity, half offshore and half onshore. Yesterday we had much of the day below 600mw of generation. It dropped as low as 219mw at one point.